On April 14, 2003, several hundred students from various universities in Tbilisi gathered outside the State Chancellery to demand the resignation of President Eduard Shevardnadze and the Georgian government. The protesters marched from their campuses to the Chancellery, where they burned Soviet Georgian flags and banners bearing the portraits of Shevardnadze, State Minister Avtandil Jorbenadze, and other leaders of the pro-government “New Block.” Their posters read “Kmara” (“Enough”), marking the beginning of the Kmara movement—an influential youth-led campaign that would soon become a key driver of continuous protests in the months leading up to the Rose Revolution.

Among government officials, only Interior Minister Koba Narchemashvili met with the students at the scene, claiming that “certain political forces are directing these students.” In a symbolic act of defiance, the protesters left ink-stained fingerprints on the walls near the Chancellery to show they were unafraid of the authorities.

The Story of Kmara

The Kmara movement’s roots go back to November 2001, when thousands of Georgians—students, journalists, and opposition figures—took to the streets in defense of the independent TV station Rustavi 2 and freedom of speech. The protests forced the resignation of four senior officials: Security Minister Vakhtang Kutateladze, Interior Minister Kakha Targamadze, Prosecutor General Gia Meparishvili, and Parliament Speaker Zurab Zhvania.

According to its members, Kmara was born from the realization among students that change required a unified, youth-led initiative. “We understood that things couldn’t go on this way. We needed something new, a name that expressed our demand clearly—and that’s ‘Kmara’ (‘Enough’),” said Levan Ekhvaia, one of the movement’s leaders, in June 2003.

The group received support from one of Georgia’s oldest civil society organizations, the Liberty Institute, founded in 1996. Kmara positioned itself as a nonviolent civic movement opposing corruption, authoritarianism, lawlessness, clan-based governance, and electoral fraud. Its 2003 informational brochure urged citizens to join the cause: “If you’ve had enough too—join Kmara, and together we will defend our future.” Attached to the brochure was a document titled “Ten Steps to Freedom,” outlining a vision for democratic reform developed by local NGOs and embraced by the Kmara activists.

Forms of Kmara’s Protest

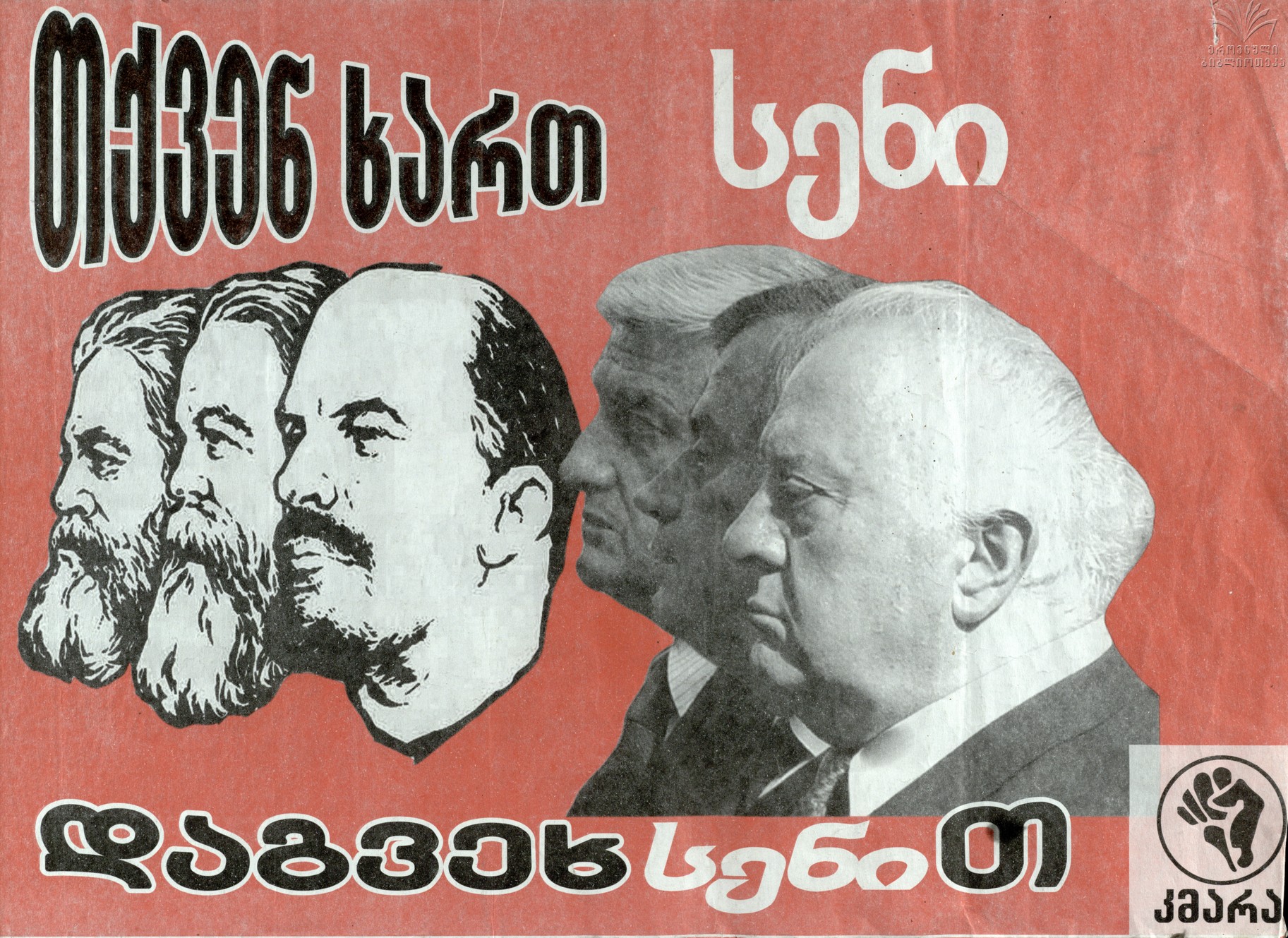

From the spring of 2003, the Kmara movement’s protests became more organized and strategic. Some of its members visited Serbia through an Open Society Foundation–funded student program, where they studied the history of local resistance movements. There, they connected with members of Otpor!, the Serbian youth movement that had helped topple Slobodan Milošević. Otpor! activists granted Kmara permission to use their iconic clenched-fist logo, which soon became the defining symbol of the Georgian movement. The Liberty Institute also played a key role in advising and supporting Kmara.

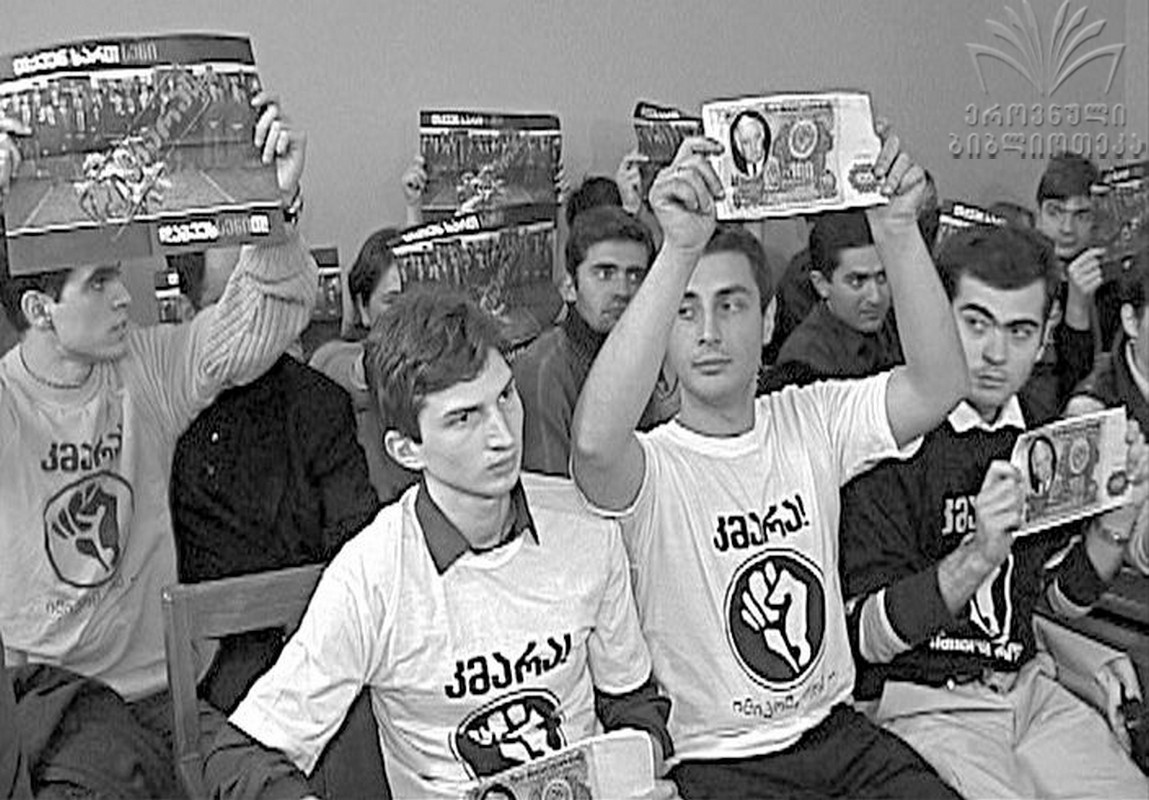

Kmara’s protest tactics were creative and diverse. Activists used visual, performative, and symbolic methods to engage the public. Every morning, Tbilisi residents woke up to find the word “Kmara” (“Enough”) painted in large letters across government buildings and city walls. Students also distributed leaflets, produced video clips, and launched public awareness campaigns. One video stated, “Electricity reaches Georgian regions twice a week—just like 80 years ago. Enough of decline.” Other slogans included “Enough of decline,” “Enough of poverty,” “You are the disease—free us,” and “Enough, because I love Georgia.” Activists wore T-shirts printed with the movement’s logo and the slogan “Because I love Georgia” on their backs.

To connect with citizens beyond street protests, Kmara members also employed community-oriented methods. As The Irish Times later noted, “Kmara activists used simple but innovative approaches to engage society—cleaning public courtyards and discussing with curious residents why the state should be doing this, or asking their grandmothers to talk to other elderly people about social issues, since many were too afraid to open their doors to young strangers.”

Kmara in 2003

On June 11, 2003, Kmara activists splashed paint on the Ministry of Internal Affairs building, leading to the seven-hour detention of nine members. They also attempted to organize rallies in Borjomi, which were blocked by authorities. On August 6, during a protest at the Ministry of Energy in Tbilisi, two activists were injured.

By the fall of 2003, Kmara’s protests merged with those of the political opposition, significantly amplifying the nationwide protest movement. As Kmara member Luka Tsuladze later told Radio Free Europe, “Our plan was never to enter power. Kmara didn’t campaign for votes or popularity. We carried the negative—pointing out problems—while opposition parties focused on giving people hope.”

Following the disputed parliamentary elections of November 2, 2003—which the opposition declared fraudulent—demonstrations became continuous and massive. “For three weeks, we held daily protests,” recalled Kmara activist Nini Gogiberidze in an interview with The Irish Times. “We organized shifts to ensure there were always enough people on Rustaveli Avenue. We prepared lunches and dinners at home for our activists.”

The wave of protests culminated in November 2003 with the Rose Revolution, which led to the resignation of President Eduard Shevardnadze and marked a turning point in Georgia’s modern history.