This AI-generated translation may not be completely accurate.

Demonstration of resettled eco-migrants in Tsalka

In the early 2000s, residents of mountainous villages in Adjara who had been affected by natural disasters were resettled in Tsalka at the initiative and invitation of President Mikheil Saakashvili. The state placed them in the houses of ethnic Greek citizens who had migrated to Greece, with the promise that these properties would later be purchased by the government. According to eco-migrants, around 3,300 families from Adjara were settled in Tsalka, but the government bought only 350 houses from the Greek owners.

After 2012, representatives of the Greek homeowners arrived in Tsalka and asked the eco-migrants to vacate their properties. Following the return of the legal owners, those resettled from Adjara left their homes in May 2013 and began living in tents in front of the Adjara government building in Batumi starting on May 13. This marked the beginning of the eco-migrants’ struggle for housing. They demanded temporary shelter, and about 144 people lived in the tents. According to the eco-migrants, others took refuge in an abandoned building nearby but were denied official permission to stay there temporarily.

On July 3, 2013, the 52nd day after returning from Tsalka to Adjara, when they still had not attracted the government’s attention, the eco-migrants began a hunger strike in front of the Adjara government building. Negotiations were led by Valeri Telia, head of the Adjara regional department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and Irakli Ch’eishvili from the Adjara government, who urged them to vacate the area. Telia promised the eco-migrants that if they stopped the hunger strike, the Chairman of the Adjara government, Archil Khabadze, and other officials would meet with them upon Khabadze’s return from a business trip on July 10. The eco-migrants continued their strike.

On the eighth day of the hunger strike, July 10, Archil Khabadze did meet with them and explained that only the Minister for Refugees and Accommodation of Georgia, Davit Darakhvelidze, had the authority to address their issue.

Several meetings were held in the Adjara government to discuss the eco-migrants’ situation. After these meetings, government representatives claimed that many of the eco-migrants’ statements were inaccurate and that most of them still had homes. They argued that the main goal of the protesters was to pressure the government into providing them with property in Adjara. To assess the situation, a government delegation was sent to Tsalka. One of its members, Deputy Minister of Health of Adjara Ramaz Jincharadze, told Batumelebi that during their visit they found that most people were not under threat of eviction: “There were a few cases, maybe three or four. We spoke to the Greek owners, and they said they wouldn’t cause problems… Their only request was for temporary housing in Batumi, but unfortunately, we had to refuse because the Autonomous Republic doesn’t have such shelters.”

The hunger strikers told journalists that they did not want housing in Adjara but rather in Tsalka, where they had originally been resettled.

On July 11, the eco-migrants from Tsalka moved into a former children’s home in the village of Urekhi, Khelvachauri Municipality. As Batumelebi reported, some quietly admitted that the government had allowed them to enter the building. Officially, eco-migrant Amiran Saginadze explained their decision: “We had to find somewhere to stay. The Ministry of Refugees and Accommodation also told us to look for a state-owned, unused building where we could live temporarily. We found this abandoned building and turned it into temporary housing. There are 120 of us living here in very poor conditions — there isn’t even a proper bathroom.”

On July 15, the eco-migrants ended their hunger strike due to deteriorating health. “After I stopped the hunger strike, I still haven’t seen a doctor. I’ve lost weight, down to 65 kilos. My blood pressure dropped, I can’t eat, I just drink coffee to keep it up,” said protester Jumber Rijvadze.

On October 10, 2013, the eco-migrants from Tsalka occupied a newly built social housing building in Batumi without permission. Residents of Batumi’s barracks also claimed rights to these apartments, saying the complex had been built for them. On October 11, they gathered in front of the building and demanded that the eco-migrants leave.

By November 5, 2014, the displaced eco-migrants were staging protests in front of the Government Chancellery in Tbilisi.

Reports from media outlets and NGOs indicated that after their unsuccessful protest in Batumi, some eco-migrants returned to Tsalka. By 2015, about 30 families were living in the former Tsalka hospital building without housing. Some were socially vulnerable families who had lost their state benefits after occupying government-owned property, leaving them without any income.

In 2016, a new program titled “Providing Housing for Eco-Migrant Families” was launched in Adjara. Media reports noted that several families received housing under this program, although it remained unclear whether those from Tsalka were included.

“The government keeps telling us that it’s a matter of waiting in line and that our turn will come, but for how long? How long can we wait? The Greek owner has already come and asked me to leave the house,” said Nugzar Paksadze from the village of Kvemo Khareba, Tsalka, during a protest on August 18, 2018.

At that time, Batumelebi reported that the Ministry of Refugees and Accommodation planned to complete the housing allocation process for Tsalka’s eco-migrants by 2020. According to the ministry, priority would be given to families in the most critical condition. Under the program, an eco-migrant could propose a home to the state, and the government would pay 25,000 GEL toward its purchase. If the property cost more, the family would cover the difference.

On October 21, 2018, eco-migrants gathered again to demand a resolution to their housing problem.

In April 2019, they resumed protests carrying signs reading “No home, no land, no future?” and “Grant eco-migrants official status.” According to eco-migrant Elguja Shavadze, 220 families from Tsalka had settled in the “Dream Town” settlement near Batumi, while 60 families had left for Iraq to work. “There were about 2,000 of us in recent years. The government keeps making promises, but in reality, only 330 families have been given homes,” said Shavadze. Locals also noted that many of them did not even have official eco-migrant status.

Kote Razmadze, deputy head of the Department for IDPs and Eco-Migrants at the Ministry of Health, claimed that most of the families in Tsalka had settled there on their own as their families expanded and that only about 300 families were actual eco-migrants. Razmadze promised that in 2019, 174 eco-migrants would receive funds to purchase homes, though he did not specify how many of them were from Tsalka.

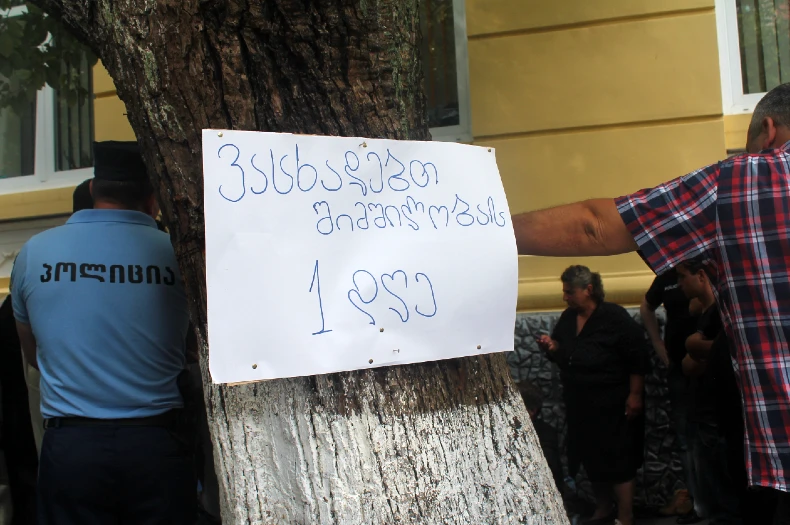

On April 17, 2019, protesters marched to the Tsalka City Hall and hung banners there, giving the authorities until May 1 to meet their demands, threatening to resume protests if ignored.

When their demands went unmet, the eco-migrants traveled from Tsalka to Tbilisi on June 11 and continued their protest in front of the Parliament. Their banners read “We demand the basics — water and land” and “Keep your promise to disaster-affected eco-migrants.” They once again urged the government to purchase homes for them and grant ownership of the land they were already using. They warned that without action, another “Dream Town” like the one in Batumi would appear, as the authorities were effectively forcing them to abandon their villages.

The protest continued on June 12. Demonstrators said that during their stay in Tbilisi, they only managed to meet with a deputy head of the Regional Management Office, who offered no concrete solutions. They lamented that even their parliamentary representatives had not met with them, saying, “No responsible official is interested in our situation or willing to give us a clear answer.”

On September 19, 2021, eco-migrants in Tsalka met with Tornike Rijvadze, Chairman of the Government of Adjara, and Sozar Subari, Chairman of the Parliamentary Committee on Regional Policy and Self-Government. After the meeting, Subari stated that they would “fight to find the best possible solution.”

A report aired by Adjara TV on January 1, 2023, showed that some eco-migrants living in Tsalka were still waiting for housing.